Platelet-Active Drugs: The Relationships Among Dose, Effectiveness, and Side Effects

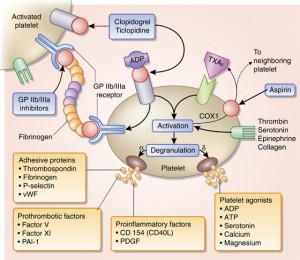

However, when contrasting the effects of aspirin in patients who have experienced an acute MI with those in patients who have experienced an acute stroke, it seems reasonable to assume that TX-mediated amplification of the platelet response to acute vascular injury plays a more important role in the coronary territory than in the cerebrovascular territory.

Long-term aspirin therapy confers a conclusive net benefit on the risk of subsequent MI, stroke, or vascular death among subjects with an intermediate-to-high risk of vascular complications. These include patients with chronic stable angina, patients with prior MI, patients with unstable angina, and patients with TIA or minor stroke, as well as other high-risk catego-ries. The proportional effects of long-term aspirin therapy on vascular events in these different clinical settings are rather homogenous, ranging between a 20% and a 25% odds reduction based on an overview of all randomized trials.

However, individual trial data show substantial heterogeneity, ranging from no statistically significant benefits in patients with peripheral vascular disease to approximately 50% risk reduction in patients with unstable angina. We interpret these findings as reflecting the variable importance of TXA2 as a mechanism amplifying the hemostatic response to plaque destabilization in different clinical settings. In terms of absolute benefit, these protective effects of aspirin translate into avoidance of a major vascular event in 50 patients per 1,000 patients with unstable angina who had been treated for 6 months and in 36 patients per 1,000 patients with prior MI, stroke, or TIA who had been treated for approximately 30 months.

For patients with different manifestations of ischemic heart or brain disease, a widespread consensus exists in defining a rather narrow range of recommended daily doses (ie, 75 to 160 mg) for the prevention of MI, stroke, or vascular death. This is supported by separate trial data in patients who were randomized to treatment with low-dose aspirin or placebo as well as by an overview of all antiplatelet trials showing no obvious dose dependence, from indirect comparisons, for the protective effects of aspirin. While this provides a rational basis for therapy at present, it is worth remembering that such indirect comparisons may fail to detect an important divergence in clinical effect. There is no convincing evidence that the dose requirement for the antithrombotic effect of aspirin may vary in different clinical settings.